quinta-feira, 28 de outubro de 2010

quarta-feira, 20 de outubro de 2010

terça-feira, 19 de outubro de 2010

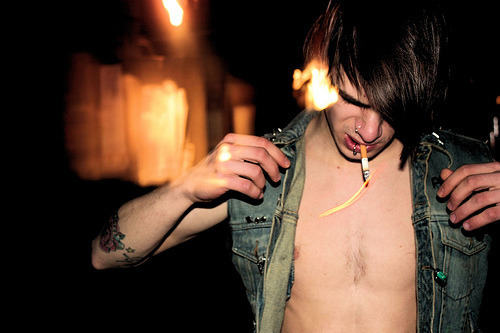

Wolfgang Tillmans

Deer Hirsch, 1995. Chromogenic print, edition 2/10, image: 10 3/16 x 15 inches (25.9 x 38.1 cm); sheet: 12 x 16 inches (30.5 x 40.6 cm). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Purchased with funds contributed by the Photography Committee 2001.33.9

via Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum:

Wolfgang Tillmans's photographs of friends, dance raves, clubs, and night life have appeared regularly in London's i-D magazine and other publications since 1989. Though his work has had a tremendous impact on the studied casualness of much recent fashion photography, Tillmans is not a "fashion photographer." If anything he is a portraitist who often photographs his friends—who appear alternately tough, vulnerable, loving, ferocious, gay, and straight—in intimate situations. Though these probing images reflect his own subjective experiences, they also operate on a more general level, recording a specific dimension of our contemporary culture. Tillmans establishes a collaborative process with his models, whom he calls "accomplices." Thus the informal look of the works belies their choreographed construction. Landscape and still-life images also play a crucial role in his oeuvre, in which half-eaten fruit, sewer rats, crumpled clothing, or urban skylines are photographed with the same dignity and attention to beauty as his human subjects. Traditional subject genres are questioned; crumpled clothing might suggest a figure or landscape, while city scenes seen from the air resemble a still life of objects.

For Tillmans, the images are only half the work; the installation or layout constitutes its completion. He affixes his prints directly to the wall with pins or tape, juxtaposing old and new images of varying sizes and mediums. He eschews standard darkroom procedures, blurring the lines between color and black and white (printing black-and-white images on color paper, for instance). Color photographs are placed next to inkjet prints and next to postcards and magazine clippings of his own images, contesting conventional hierarchies of scale and subject matter while drawing focus to the materiality of the photographic medium—all within a carefully composed environment that seems to disdain permanency.

Thomas Struth

Milan Cathedral (Interior) (Mailänder Dom [Innen]), 1998. Silver dye bleach print, face-mounted to acrylic, edition 4/10, image: 68 3/8 x 86 3/8 inches (173.7 x 219.4 cm); sheet: 71 1/8 x 89 inches (180.7 x 226.1 cm). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Purchased with funds contributed by the Harriett Ames Charitable Trust and the International Director's Council and Executive Committee Members: Edythe Broad, Henry Buhl, Elaine Terner Cooper, Gail May Engelberg, Linda Fischbach, Ronnie Heyman, Dakis Joannou, Cindy Johnson, Barbara Lane, Linda Macklowe, Peter Norton, Willem Peppler, Denise Rich, Simonetta Seragnoli, David Teiger, Ginny Williams, Elliot K. Wolk 99.5301. © Thomas Struth

Struth's early black-and-white cityscapes—images of barren urban streets photographed from one central perspective—elicit comparisons to Bernd and Hilla Becher's typological studies of industrial structures. Struth had studied with the couple at the Academy of Fine Arts in Düsseldorf during the 1970s and shared their systematic, objective approach to subject matter. But it was another of Struth's professors at the Academy, Gerhard Richter, who made a lasting impression on the young artist's work. Richter's conceptual engagement with the photographic and his practice of working in simultaneous series is evident in Struth's own ongoing series of landscapes, street scenes, flowers, portraits, museum interiors, and places of worship.The Richter Family I, Cologne is a penetrating depiction of the artist's former mentor with his wife and young children.

Struth's photographs of historic churches and temples, which function today as both religious sites and tourist destinations, always include people. Like his museum interiors, images of places such as San Zaccaria in Venice and the Buddhist monastery Todai-Ji in Nara, Japan, portray visitors in various stages of absorption. In Milan Cathedral (Interior), these visitors turn away from the camera to survey their environment, observe the Renaissance paintings, study their guidebooks, or pray. Shot at an oblique angle and lit with the utmost clarity, this dynamic composition captures both the complexity of the cathedral's celebrated architecture and the many separate vignettes being enacted by the individuals present at the moment the photograph was taken.

Sam Taylor-Wood

Soliloquy I, 1998. Two chromogenic prints, diptych, edition 4/6, 82 1/4 x 101 inches (208.9 x 256.5 cm) overall . Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Partial and promised gift, David Teiger 2000.104

Soliloquy II, 1998. Two chromogenic prints, diptych, edition 2/6, 82 1/4 x 101 inches (208.9 x 256.5 cm) overall. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Gift, The Bohen Foundation 2001.285

Soliloquy III, 1998. Two chromogenic prints, diptych, edition 4/6, 88 x 101 inches (223.5 x 256.5 cm) overall. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Partial and promised gift, David Teiger 2000.105

Soliloquy IV, 1998. Two chromogenic prints, diptych, edition 2/6, 88 x 101 inches (223.5 x 256.5 cm) overall. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Gift, The Bohen Foundation 2001.286

Sam Taylor-Wood's photographs and film installations depict human dramas and isolated emotional instances, such as a quarreling couple and tense social gatherings—people in solitary, awkward, or vulnerable moments. These psychologically charged narratives are often presented on a grand scale, in room-encompassing video projections or 360-degree photographic panoramas accompanied by sound tracks. In her Soliloquy series (1998–99), Taylor-Wood's cinematic sensibility is coupled with references to the history of painting. The photographs are structured like Renaissance altarpieces and predellas (iconographically related panels attached along altarpiece bases): a large-format portrait is paired with a panoramic image below. Captured in a personal moment of self-reflection, asleep, or daydreaming, the subjects are often depicted in poses borrowed from well-known paintings. In Soliloquy I(1998), for example, the languid pose of the sleeping man recalls that of the dying poet in Henry Wallis's The Death of Chatterton (1865), and in Soliloquy III (1998), the reclining nude recalls Velázquez's Rokeby Venus (1650).

Typically, the people portrayed in Taylor-Wood's works are self-absorbed and seemingly detached from their own environment. The title of this series is derived from the name of the theatrical monologue during which an actor disrupts the narrative to directly address the audience with some commentary on the story. That state of deliberate disengagement is implied by the dual images comprising each work: the larger photo represents the conscious state of the subject, while the filmic tableau below provides a register of his or her subconscious fantasies. Sometimes the characters reappear in this imaginary world—the nude from Soliloquy III sits at the back of the loft space, dressed in red, observing at a distance the erotic activities that occur before her. In Soliloquy II (1998), the shirtless male figure, who, in the large image, is surrounded by dogs (in a pose reminiscent of a Thomas Gainsborough hunting portrait), appears seated with a dog in the corner of the bathhouse setting of the “predella.” Reality invades fantasy when a dog's tail or the sleeping figure's hand crosses from the top image into the panel below, scale unchanged—a grotesque intrusion into the imaginary realm.

sexta-feira, 15 de outubro de 2010

quinta-feira, 14 de outubro de 2010

quarta-feira, 13 de outubro de 2010

terça-feira, 12 de outubro de 2010

segunda-feira, 11 de outubro de 2010

Assinar:

Postagens (Atom)